We’ve heard for years that America has a shortage of doctors. According to projections from the AAMC, if we do not take steps to address this issue, we can expect shortages of between 38,000 and 124,000 physicians by the year 2034. But why is it so difficult to increase the number of physicians in the U.S.?

Here are 5 reasons why America has so few doctors:

- Length of Training

- Cost of Training

- Limited Number of Residency Spots

- Limitations of Importing Physicians

- Aging Population

1 | Length of Training

To start, the United States has one of the longest training pathways to becoming a physician in any developed country. Becoming a doctor in the U.S. requires you to complete a 4-year bachelor’s degree followed by 4 years of medical school and 3 to 7 years of residency.

In contrast, many European countries including the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and Switzerland do not require a bachelor’s degree and instead allow students to matriculate into medical school directly after high school. In general, medical school in these countries is 5 to 6 years in duration, after which students will complete residency training lasting an additional 3 to 8 years depending on the country and the particular specialty.

If we do some simple calculations, the shortest amount of time it would take to become a physician in the United States after high school is around 11 years – that’s 4 years to get your bachelor’s degree plus 4 years of medical school and three years of residency. In contrast, the shortest pathway to becoming a physician in many European countries, such as Switzerland for example, would be 6 years of medical school followed by three years of residency for a total of 9 years.

Medical school admissions in the U.S. are also highly competitive, which often adds additional years to the already long training process. According to data from the AAMC, AACOM, and TMDSAS, in any given year, only around 36% of applicants to U.S. MD and DO schools matriculate and only around 25% of applicants to Texas medical schools matriculate.

Although there are some countries where it is more competitive to become a doctor than in the U.S., it is not uncommon for U.S. premeds to apply to medical school multiple times before getting accepted. And because medical school applications occur once per year, each unsuccessful application cycle adds an additional year to the already lengthy training process.

2 | Cost of Training

Next is the exorbitant cost of medical training.

Although physicians in the U.S. earn higher salaries on average than their European counterparts at around $242,000 per year for primary care physicians and $344,000 per year for specialists, the cost of becoming a physician in the U.S. is also significantly higher.

As of 2022, the average cost of medical school tuition in the United States is approximately $55,000 per year with some schools charging more than $70,000 per year at the upper end.

It’s no surprise then that the average medical student graduates with around $242,000 of student loan debt with some students having over $400,000 in student debt between tuition and living costs over 4 years of medical school. It’s only getting more expensive too as the average cost of medical school rises by approximately $1,500 each year.

Although there are more premeds than there are medical school spots, as demonstrated by the roughly 36% matriculation rate, the cost of medical education can be prohibitive for many students – particularly minority students and those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. According to the U.S. Census, Black and Hispanic individuals are between one and a half to two times more likely to experience poverty than White or Asian individuals. As such, many of these students may be dissuaded from pursuing medicine due to the high cost of medical education.

This is an important factor to consider as research has shown that physicians that come from poor or minority backgrounds are more likely to practice in underserved communities, where the need for physicians is the greatest.

3 | Limited Number of Residency Spots

Perhaps the largest factor limiting our ability to produce more physicians, however, is the limited number of residency positions offered each year.

To practice medicine as a physician in the United States, you must complete 3 to 7 years of residency training after medical school. The issue is that there are more medical students graduating each year than there are residency positions to accommodate them.

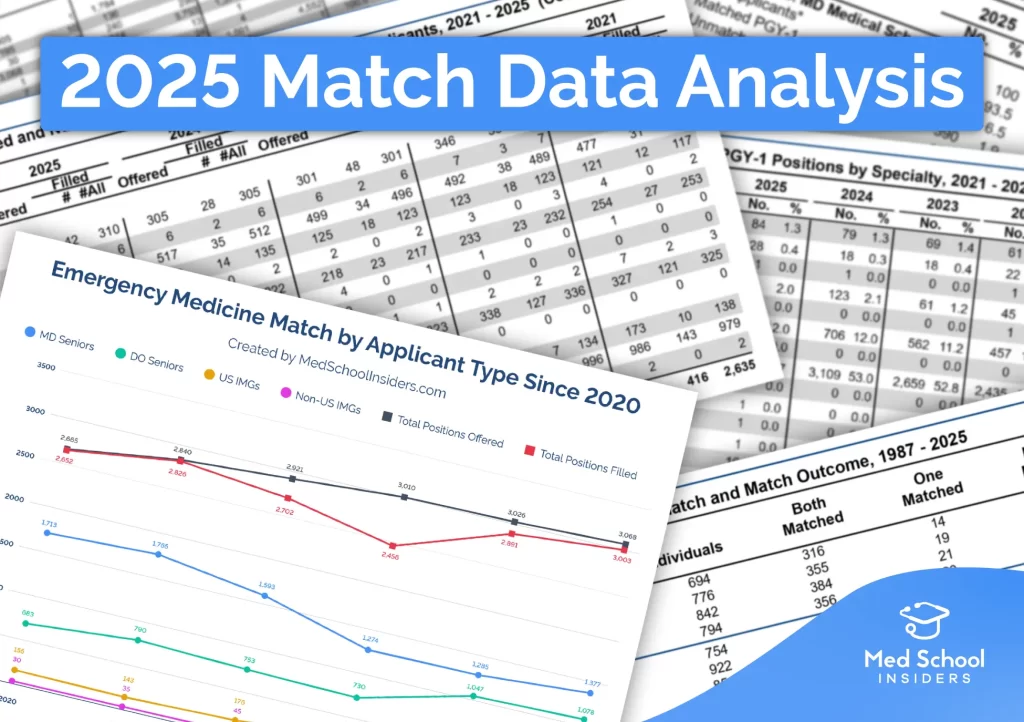

During the most recent 2022 NRMP Match, there were approximately 6,400 medical students that applied for residency that went unmatched even after the Supplemental Offer and Acceptance Program, or SOAP. That’s approximately 15% of the total number of active applicants in 2022.

These students will have to put their training on hold for a year and do research, or some other job, while they strengthen their application for the following cycle. There’s a simple solution then. We just need to increase the number of residency spots. Easy, right? Not quite.

The majority of funding for residency programs comes from Medicare. The problem with this is that there were certain caps on Medicare GME funding imposed in 1997 which have largely frozen in place the facilities eligible to receive funding. This, in turn, has greatly hindered our ability to open new residency programs.

This is slowly changing with the recent 2021 Consolidated Appropriations Act which will have Medicare provide an additional 1,000 funded slots over 5 years starting in 2023; however, many are concerned that the existing system still does a poor job at creating new residency programs for a variety of other reasons.

To start, the majority of residency programs are in large metropolitan areas where the cost of living is high. As such, each dollar spent on funding residency programs doesn’t go as far as it would if these programs were in areas with lower costs of living.

It would make much more sense to establish residency programs in rural communities where care could be delivered more efficiently to the patients that need it most. Despite this, residency programs are much more abundant in large metropolitan areas compared to rural areas.

This is largely a consequence of large teaching hospitals in metropolitan areas having more leverage with private insurers to gain higher reimbursement rates for residents. Residents implicitly finance a portion of their training through their contributions to patient care. As such, there is often less financial risk to hospitals starting residency programs in these big metropolitan areas as they often receive higher reimbursement rates for services provided by residents.

In addition, there is often more financial incentive to fund specialized residency programs as opposed to primary care specialties, despite the latter being in greater need, as reimbursement rates for specialists tend to be much higher.

For these reasons, just throwing more money at the problem of the limited number of residency positions may not be sufficient.

4 | Limitations of Importing Physicians

That being said, increasing the number of physicians trained in the U.S. is only one solution to the physician shortage. Another solution is to import physicians from other countries to practice in the United States.

The issue is that there is a lot of red tape that foreign-trained physicians must navigate to practice medicine in the United States. In many states, foreign-trained physicians are required to take the USMLE Step exams and repeat residency training, which can be a huge barrier to entry for physicians who have been practicing for many years and are well established in their specialty.

According to a 2020 article in the Annals of Internal Medicine, International Medical Graduates, or IMGs, “constitute about 25% of all actively practicing specialists in the United States, and most work in rural and underserved areas throughout the country.

This may sound like a lot; however, many IMGs are only here on temporary H-1B and J-1 visas while completing residency training. IMGs that hold a J-1 visa are required to return to their home country for 2 years after completing their residency or finish a 3-year “waiver” position in an underserved area before they can apply for permanent status or a green card. IMGs holding an H-1B visa may apply for a green card and permanent residence after they complete their residency.

That being said, just because they are eligible for a green card does not mean that they will receive one. Green cards issued under the “employment-based” category, such as for residents, have a total cap of only 140,000 green cards per year with a fixed cap of 7% allotted to each country.

In addition, IMGs do not receive any preferential treatment in obtaining their green card for being a physician. And even after receiving a green card, there are multiple hoops to jump through to practice as a physician permanently in the U.S.

5 | Aging Population

Lastly, a growing and aging population combined with an aging workforce of doctors nearing retirement has further exacerbated the issue of physician shortages. The AAMC estimates that within the next decade, more than 2 out of every 5 practicing physicians will be over the age of 65.

In addition, physician burnout is a huge issue within medicine that has been further exacerbated over the past few years as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. These issues may lead some physicians to decrease their hours or even leave the profession as a whole earlier than anticipated further straining our physician workforce.

This is another big reason why we need to take steps toward increasing the number of physicians in the United States. The long hours and difficult schedules that resident physicians and attendings work are not a matter of necessity, but rather a byproduct of our lack of physicians.

Some physicians oppose training more medical students and residents or recruiting foreign doctors as they fear it will decrease their salaries. Although this is a reasonable concern, having more doctors is likely to make life better for U.S. physicians. By sacrificing a bit of pay, they may be able to avoid 60+ hour workweeks and having to spend nights and weekends on-call.

That being said, the one area that we need to remain cautious about as we take steps to address the physician shortage is the rising cost of medical education. If the cost of medical education continues to increase at the current rate and salaries for physicians start to decrease, we may end up with a generation of physicians with massive debt that they struggle to pay back. This is one of many factors that we will need to consider as we work to solve this problem.

As you can see, solving the issue of physician shortages in the U.S. is not just a matter of “training more doctors.” It is a complex issue with many different factors that will require an equally complex and multifactorial approach.

We need leaders and policymakers to take a good hard look at the state of medical education and physicians in the U.S. and start making steps towards addressing issues like the rising cost of medical education, physician burnout, and the lack of residency positions. Only then will we be able to meet the growing demands for physicians in the United States.

If you enjoyed this article, be sure to check out my piece on The Real Cost of Medical School or Burnout in Medical Students and Residents.

This Post Has One Comment

What are the reasons why the United States has a significant shortage of doctors?

Regard Telkom University