Lowest Paid Medical Specialties in 2026

We break down the lowest-paid medical specialties in 2026, including average salaries, training length, lifestyle tradeoffs, and why compensation varies across fields.

Many premed and medical students think they want to become surgeons. But deep down, there’s a nagging question: Do I actually have what it takes?

Surgery demands something most other specialties don’t—a specific combination of traits that can’t be taught or faked. You either have them, or you’ll burn out trying to pretend you do.

Students are drawn to surgery for obvious reasons. Most surgeons make over $500,000 annually, with some earning upwards of $750,000. Surgery represents prestige, skill, and the apex of medical accomplishment.

But here’s the problem: most students decide they want to be surgeons long before they understand the reality of surgery. What they’re chasing is an idea, not the truth.

By the end of this post, you’ll know whether or not you’re cut out to be a surgeon, and also the single factor that caused me to quit plastic surgery.

The first sign you’re built for surgery is that you naturally operate with obsessive precision.

In most medical specialties, approximation works. An internist can try a medication, see how the patient responds, and adjust accordingly. A psychiatrist can modify therapy approaches over time. But surgery allows zero margin for error. One millimeter off during a delicate nerve repair can mean the difference between a patient regaining function or living with permanent disability.

This isn’t about having steady hands. It’s about a fundamental personality trait where you strive for perfection. You double-check your work not because you’re insecure, but because you instinctively notice when the smallest detail is out of place or misaligned.

The surgeons who excel are the ones who can’t help but notice these details. They practice knot-tying until muscle memory takes over, not because they have to, but because imperfection bothers them at a core level.

This obsession with precision extends beyond the operating room. Surgical residents must possess a photographic precision in anatomy, understand complex three-dimensional relationships, and plan procedures with meticulous, military-like preparation.

If you find satisfaction in getting things exactly right, this might indicate surgical aptitude. But if you’re comfortable with approximation, if “close enough” feels fine to you, surgery will be torture.

Which brings us to the next crucial question: Do you actually enjoy the process of doing procedures, or just the idea of being a surgeon?

The second sign is that you genuinely love performing procedures, not just observing them or talking about them.

There’s a massive difference between being impressed by a complex operation and genuinely enjoying the process of performing procedures day after day.

I initially thought I wanted to become a gastroenterologist because of my Crohn’s colitis, a type of inflammatory bowel disease. But during clinical rotations, I realized something crucial: while I enjoyed the hands-on aspects of endoscopies and biopsies, they felt extremely limited.

I craved more challenge and wanted to spend most of my time in the OR, not just performing simpler outpatient procedures a day or two per week. That’s when I understood I needed a procedure-focused specialty, which led me to plastic surgery.

But here’s the reality check: surgery isn’t just the exciting, complex cases you see on medical TV shows. The vast majority are bread-and-butter procedures. General surgeons do their hundredth appendectomy. Orthopedic surgeons repair their thousandth torn ACL.

The question isn’t whether you find that first appendectomy interesting—it’s whether you’d still find the 50th one engaging. Can you derive satisfaction from perfecting your technique on routine procedures, or do you need constant novelty to stay motivated?

The best way to figure this out is through extensive exposure to various specialties early in medical school. We have a detailed guide on how to choose your ideal medical specialty, which walks you through six specific steps to find the right match.

But loving procedures is only part of the equation. Surgery is also highly competitive.

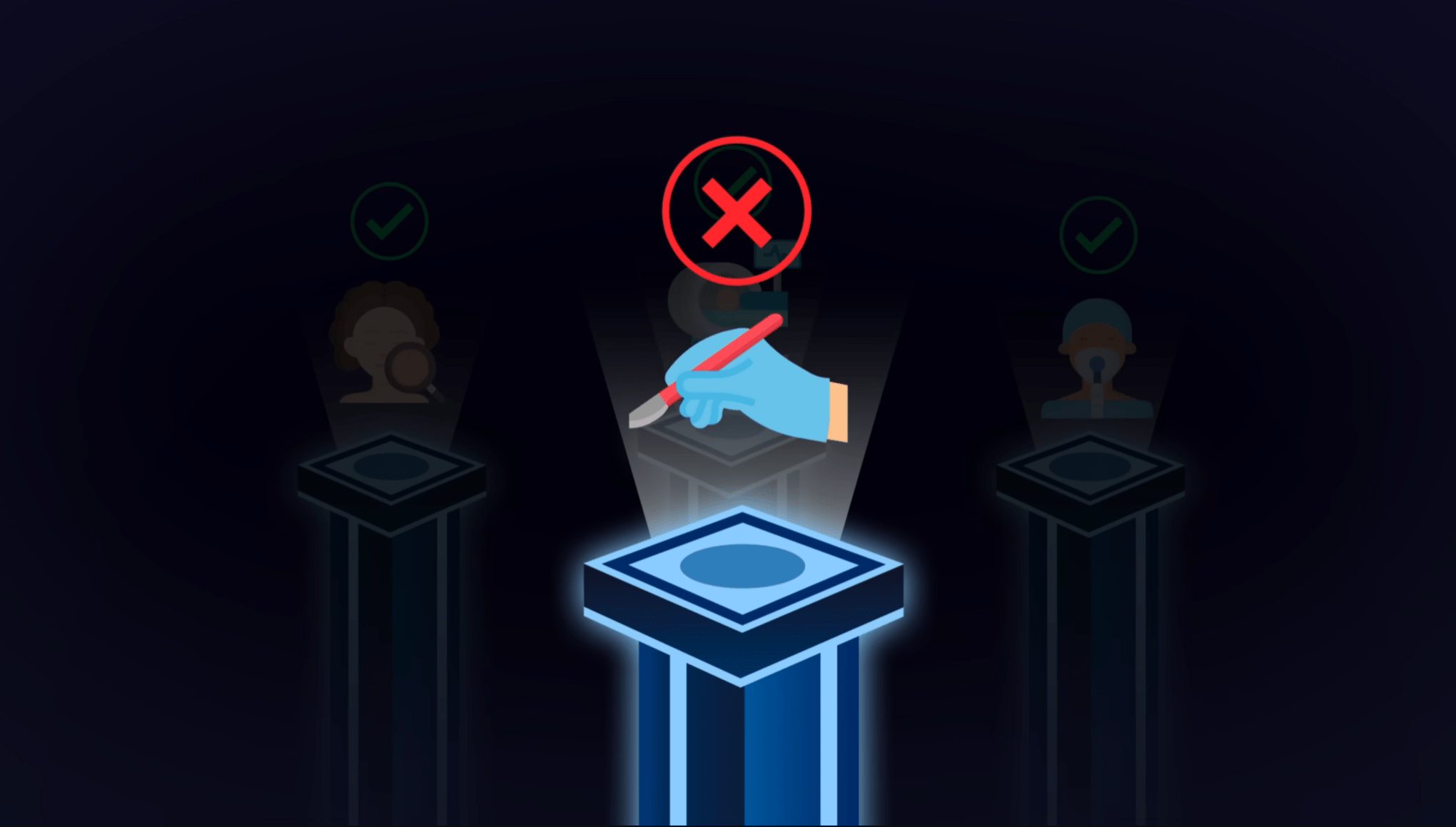

The third sign you’re built for surgery is that you not only handle intense competition—you thrive on it.

Let’s be clear about what you’re up against. If you visit specialtyranking.com, you’ll notice something striking: there are no surgical specialties in the bottom tier of competitiveness. Every single surgical specialty ranks among the most difficult to match into.

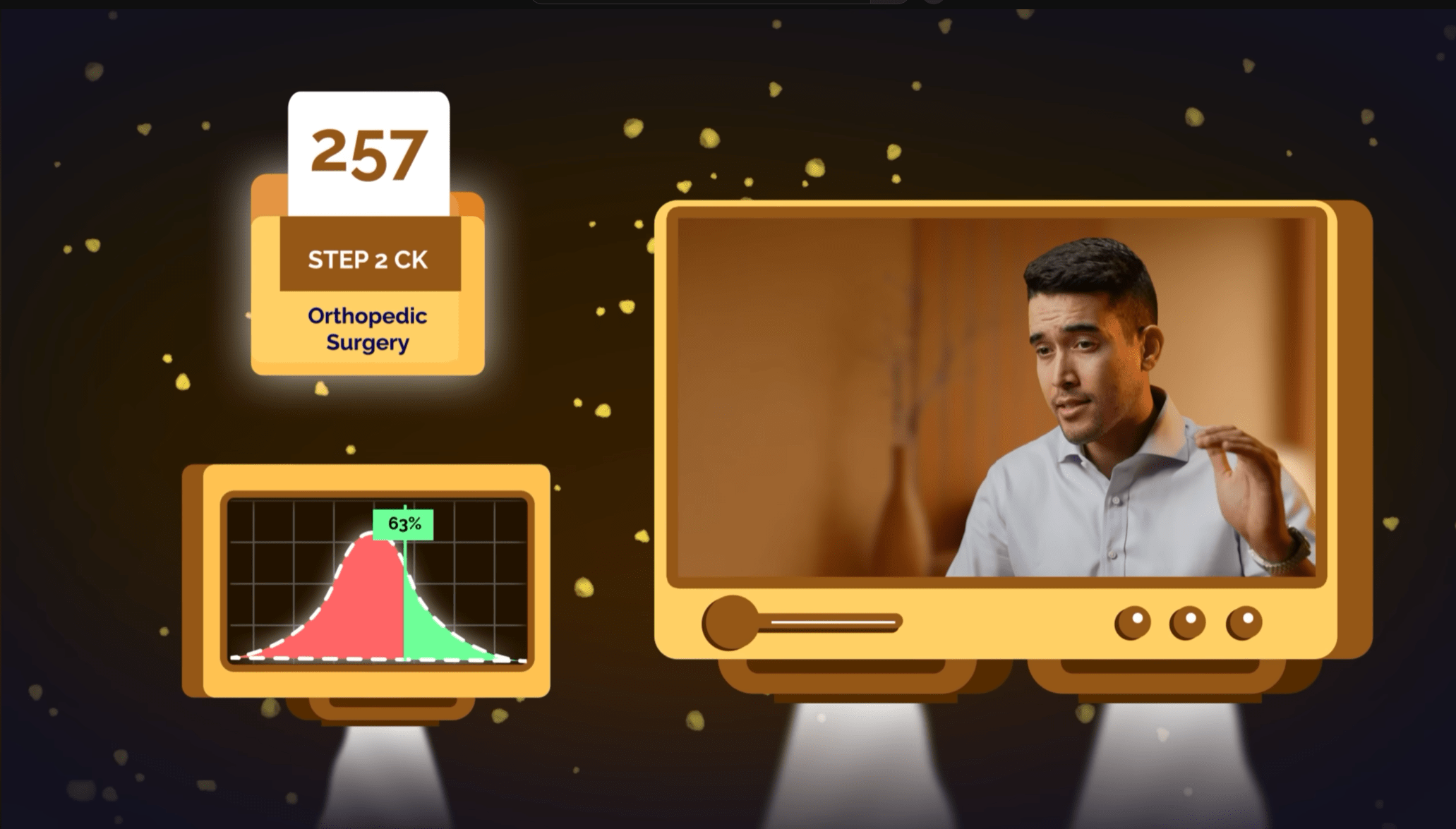

Take orthopedic surgery. The average successful applicant has a Step 2 CK score of 257, which puts them above the 63rd percentile of all test-takers. They average 24 research items and have a 73% match rate.

Plastic surgery is similarly brutal. Successful applicants typically have an average of 35 research publications, presentations, and abstracts, a Step 2 score of 256, and a 75% match rate.

Neurosurgery is currently the most competitive surgical specialty, with a 69% match rate with an average of 37 research items and a Step 2 score of 255. These numbers represent years of sacrifice—weekends in research labs, evenings writing papers, and summers dedicated to surgical research instead of taking time off.

Even so-called “easier” surgical specialties like general surgery require Step 2 scores of 253 and around 11 research items, with an 82% match rate. Compare this to family medicine’s 99% match rate, average Step 2 score of 244, and only four research items.

The students who thrive in this environment find motivation in high-stakes competition. They’re energized by the challenge rather than overwhelmed by it.

Check out specialtyranking.com for yourself to see these brutal statistics. You can manipulate the ranking rubric yourself and review official NRMP data from the past decade to see how competition has intensified over time.

But even if you love competition, succeeding requires something even more fundamental: an unrelenting work ethic.

The fourth sign is that you have a work ethic and discipline that operate on a different level from your peers, pun intended.

Let’s talk about what it takes to accumulate 30+ research items by the time you apply to surgical residency. It means starting early in medical school and maintaining productivity throughout your training.

Successful surgical applicants juggle multiple research projects simultaneously while excelling in their coursework and clinical rotations.

But research is just one component. Those impressive Step 2 CK scores don’t happen from a few weeks of cramming. They’re the result of years of disciplined study habits that often start back with MCAT preparation. If you struggled to achieve a competitive MCAT score or required multiple attempts, this may be a red flag for the demands of surgical training.

The discipline required extends beyond academics. Surgical residents maintain extensive surgical case logs, prepare presentations, and often continue research activities—all while working 80-hour weeks.

Surgical training demands that you operate at peak performance across all domains simultaneously and across years. If this sounds exhausting rather than challenging, surgery may not be the best fit.

But work ethic alone isn’t enough. There’s one more fundamental trait that separates those who flourish in surgery from those who merely survive.

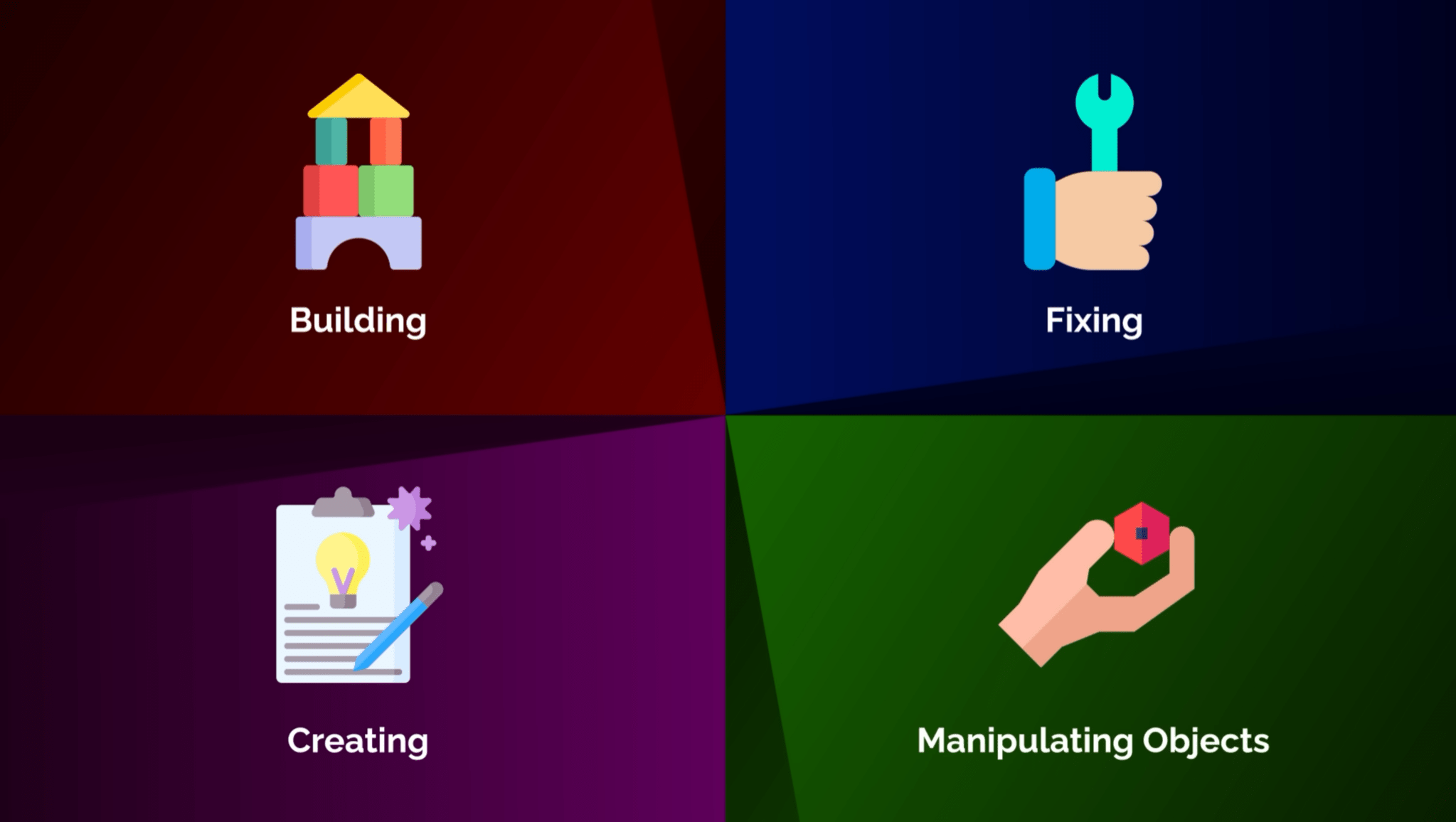

The final sign you’re built for surgery is that you have an innate need to work with your hands—not just the ability, but an actual psychological need.

This isn’t about manual dexterity that can be learned. It’s about a fundamental drive to create, build, and fix things with your hands.

I’ve always had this need. As a kid, I loved drawing and was constantly building things. In medical school, it was the physical act of surgery that satisfied something deep in me. Even now, I find myself gravitating back to hands-on hobbies—getting back into drawing, calligraphy, working on cars. That need doesn’t go away.

I remember reading “Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance” and thinking, yes—that’s exactly it. That craftsmanlike feeling Pirsig describes when you’re totally absorbed in working with your hands. Surgery is precisely that, just with higher stakes.

Look at your own history. Have you always been drawn to activities that require working with your hands? Do you enjoy building, fixing, creating, or manipulating objects with precision?

The surgeons who truly excel are those who can’t imagine practicing medicine any other way. For them, the idea of spending their career primarily talking to patients or reading studies feels incomplete. They need the immediate, tactile feedback that only surgery provides.

If you don’t have this innate drive to work with your hands, surgery will eventually feel like technical torture. But if you do have this need—if working with your hands feels as natural as breathing—then a specialty without procedures will never fully satisfy you.

You might be wondering which of the five factors didn’t align for me. After all, I quit plastic surgery, and if you’ve been here a long time, then you probably know the first five weren’t the issue.

The truth is, I loved surgery. I had the drive, the precision, the work ethic, the hands-on obsession. But there was one bonus reason that ultimately pulled me away: surgery demands all of you.

There’s no such thing as a side hustle surgeon. At least, not if you want to be a great one. Surgery isn’t just a job. It’s an all-consuming lifestyle. And while some medical specialties leave room for balance, like dermatology, radiology, or anesthesiology, surgery doesn’t. It’s not designed for divided focus.

I learned that the hard way. I was trying to do both—push through a six-year plastic surgery residency while simultaneously building businesses on the side. I was optimizing every minute of my day and night, sleeping only four hours a night, taking no days off. Eventually, I realized this wasn’t a time management problem. It was a human limitation problem.

No matter how much discipline I threw at it, trying to be all in on two life paths at once—surgery and entrepreneurship—wasn’t sustainable. And if I had continued, I would have burned out or failed at both. So I chose the one that aligned most with who I am.

Only you can determine whether these five signs describe who you are at your core, or who you think you should be.

Want to see exactly how competitive your surgical specialty of interest really is? Check out specialtyranking.com to explore the latest match data and see where you stack up against the competition.

We break down the lowest-paid medical specialties in 2026, including average salaries, training length, lifestyle tradeoffs, and why compensation varies across fields.

Use our medical school application guide to gain an understanding of the application timeline, what’s included, mistakes to avoid, and what happens next.